A clinician sees a Somali patient with a primary complaint of back pain and, following an exam, prescribes a traditional course of western medical action. The patient, however, is reluctant to act on the medical advice because he thinks his back pain is caused by a bad relationship with his parents or guilt over something he did. “It is always good (for clinicians) to have some knowledge about their patient’s culture, to know who they are dealing with,” says Fozia Abrar, MD, of Minneapolis. “It might cost time and money, but you save more money by not getting a misdiagnosis, by improving quality of care.”

Suffering from bacterial gastritis, a Somali woman in Minnesota visits several providers but does not take the medication they prescribe. When met with a smile and a greeting in her native language by Dr. Abrar, the patient complies with the same treatment recommended by the previous providers—Dr. Abrar successfully persuaded the patient to fill a prescription and take the medication because of her knowledge of the patient’s culture. This situation is not new or unique—medical anthropologist and psychiatrist Arthur Kleinman, MD, has spent 30 years championing cultural issues in medicine. He says a great body of evidence shows culture does matter in clinical care.

Every cultural group has traditional health beliefs that shape members’ perspectives about wellness. The increasingly diverse, twenty-first-century patient population requires clear communication and practitioner awareness of patient health perspectives in order to

significantly impact patient satisfaction, safety, compliance, and outcomes.Organizational Culture, Patient Satisfaction, and Safety

Organizational culture informs every worker whether patient satisfaction is a key value. By influencing employee behavior and how employees are treated, culture drives employee effectiveness, safety, and whether employees take advantage of opportunities as they arise. Organizations that dedicate additional employee resources to patient safety signal to employees that both employee effectiveness and patient safety are high priority. In other words, organizational values and beliefs guide employee commitment to patient and worker satisfaction. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: 2016 User Comparative Database Report, patient safety improved more at hospitals where they increased employment of staff who reported incidents, compared to hospitals that did not expand the number of employees who reported incidents.

At Atrius Health, a Massachusetts ambulatory care provider with 36 locations, staff can report safety events while updating existing electronic health records (EHRs). This reporting mechanism has increased the number of reported events, and as many as 30% of events reported monthly come in through the EHR tool, according to Ailish Wilkie, patient safety and risk management director for Atrius Health.

In other words, employee accountability shapes workplace and organizational culture.

Patient Culture, Provider Culture

In addition to the effect workplace culture has on patient satisfaction and employee competency, two additional areas of culture impact health care effectiveness. Both a patient’s cultural background and the provider’s scientific/medical culture inform patient and provider wellness perspectives. If patient compliance with the treatment plan is the goal, providers need to understand the patient’s cultural identity.

In addition to the effect workplace culture has on patient satisfaction and employee competency, two additional areas of culture impact health care effectiveness. Both a patient’s cultural background and the provider’s scientific/medical culture inform patient and provider wellness perspectives. If patient compliance with the treatment plan is the goal, providers need to understand the patient’s cultural identity.

By the same token, patients need to know that their perspectives are respected. Few health care observational studies have reported sufficient information to support the claim of provider bias, but a 2006 study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine reported that most internal medicine residents gain cross-cultural skills through informal training, and most stated that delivery of high-quality, cross-cultural care was important but were skeptical about the expectation of learning every little detail about all cultures. Barriers to cross-cultural care included lack of time, not knowing enough about the religion or ethnic group of the patient they were caring for, and/or dealing with belief systems which are different than their own.

A 2000 study in Social Science and Medicine found that physicians rated minority patients more negatively than White patients; the study also reported that physicians viewed minorities as non-compliant and more likely to engage in risky health behaviors. Clearly, providers need reliable resources to add to their understanding of the patient’s perspective.

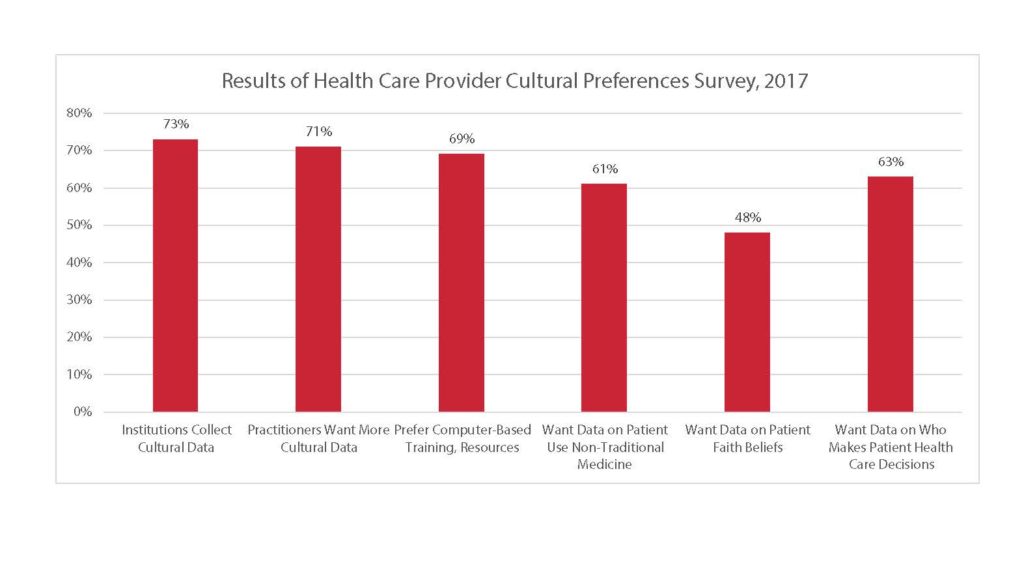

A 2017 survey of 111 health care providers revealed where providers currently turn to access cultural training and information, and what types of information providers need when they are unsure/unaware of the patient’s cultural profile and its implications for treatment decisions, patient compliance, and safety outcomes. The survey found that providers want more data on their patients’ use of nontraditional medicine; their faith beliefs; and who the health care decision-makers are.

Diversity and Disparities

An increase in racial and ethnic minority health professionals provides greater opportunity for minority patients to see a practitioner who speaks their primary language or is from their own racial or ethnic background. This can improve the quality of communication, patient safety, satisfaction, compliance, and outcomes. In addition to increasing the diversity of practitioners, hospitals are working to improve hiring diversity, employee cultural awareness, and organizational culture.

In 2015, The Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) commissioned a national survey of hospitals and health systems to quantify the actions they are taking to promote diversity in leadership and governance, and reduce health care disparities. Data for this project were collected through a national survey mailed to the CEOs of 6,338 U.S. registered hospitals. The response rate was 17.1%, with the sample generally representative of all hospitals.

Minorities represent a reported 32% of patients in hospitals that responded to the survey, and 37% of the U.S. population, according to other national surveys. In contrast, the HRET survey data show that minorities represent only 14% of hospital board membership, 14% of executive leadership positions, and 15% of first- and mid-level positions.

As a sign of progress, though, nearly half of hospitals surveyed had a plan to recruit and retain a diverse workforce matching their patient population. Further, 42% said they implemented a program to find diverse employees in the organization worthy of promotion.

Cultural Data Collection

The HRET data show that 98% of hospitals are collecting patient data on race. Additionally, other areas of data collection included ethnicity (95%) and first language (94%). But, the percentage of hospitals that correlated the impact these factors have to the delivery of care was a mere 18%. Remarkably, in 2011 only 20% of hospitals analyzed clinical quality indicators by race and ethnicity to identify patterns, whereas 14% looked at hospital readmissions, and 8% analyzed medical errors.

A serious flaw in the HRET survey was zero data collected on hospital patient national origin. The report listed myriad reasons why hospitals might be failing to meaningfully use the data, such as fearing potential liability issues after publicly acknowledging disparities in care, concerns about the public relations backlash, and a lack of knowledge in developing clinical programs that would reduce or eliminate inequalities. Plus, some hospitals noted the lack of a “diversity champion” on their staff to help lead the effort.

Hospitals seem to be making progress in educating staff on diversity, with 80% providing cultural competence training during orientation and 79% offering continuing education opportunities on cultural competency, according to the survey.

What’s Next?

Hospitals have begun to include leadership goals designed to reduce care disparities by implementing diversity initiatives such as: allocating adequate resources to ensure cultural competency/diversity initiatives are sustainable; incorporating diversity management into budget planning and implementation process; increasing hospital board diversity to reflect that of its patient population; board members demonstrating completion of diversity training; developing plans specifically to increase ethnic, racial, and cultural diversity of executive and mid-level management teams; and executive compensation tied to diversity goals.

Beyond the C-suite, hospitals are developing diversity plans with initiatives that include diversity goals in hiring manager performance expectations; implementation of programs to identify diverse, talented employees within the organization for promotion; documented plans to recruit and retain a diverse workforce that reflects the organization’s patient population; required employee attendance at diversity training; hospital collaboration with other health care organizations to improve health care workforce training and educational programs in the communities served; and education of all clinical staff during orientation about how to address unique cultural and linguistic factors affecting the care of diverse patients and communities.

This increased implementation of appropriate health care and adherence to effective diversity and cultural education programs at every level of health care will ultimately result in improved patient satisfaction, compliance, hospital safety, and patient health outcomes.