The American Nurse

Americans possess unwavering faith in registered nurses. Year after year, nurses top the list of most trusted professionals. But ask most people just what nurses do and their answers lack clarity, conviction, and a clear-eyed understanding of nursing’s sundry roles.

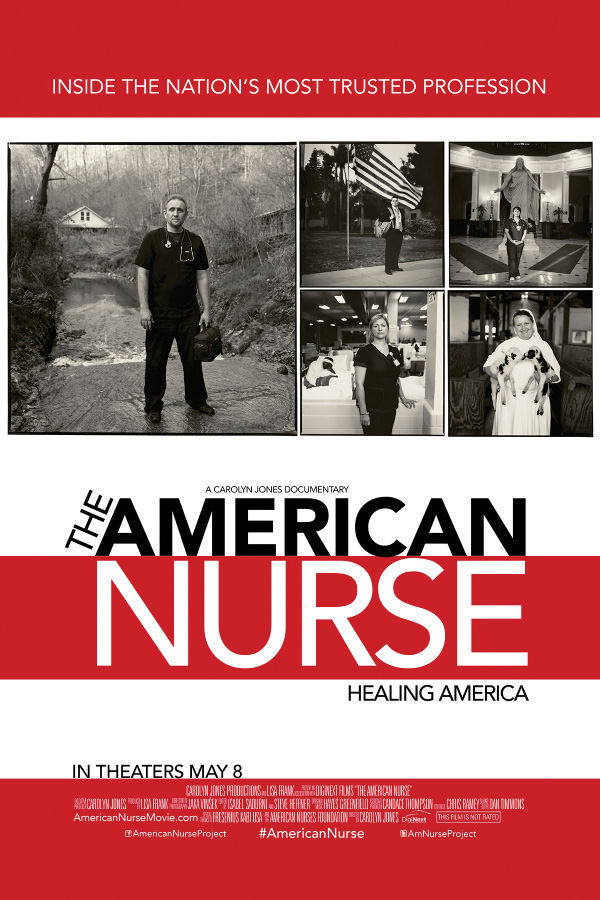

The American Nurse: Healing America, a documentary film that premiered during National Nurses Week in May, teaches audiences about the diversity and scope of nursing and the critical roles these warriors of healing play during the most vulnerable moments of life, says award-winning photojournalist and filmmaker Carolyn Jones.

“These nurses will knock your socks off. They were so open and free with sharing their inner thoughts and souls, and I am very grateful, and we are lucky to have it on film,” says Jones, whose high-energy persona was palpable during a phone interview.

Two years in the making, the film follows the path of nurses working in hospitals, rural homes, city streets, helicopters, and prisons. The film captures nurses on the front lines of the biggest issues facing America—poverty, aging, war, and justice.

“The main thing is to raise the volume on the voices of nurses in this country,” says Jones, whose film follows the lives and work of five nurses who represent a spectrum of the country and its health care system. “They are a treasure chest of unbelievably rich information. They can make our hospitals run better; they can make schools run better; they can make our communities richer; and they can make the end of life so much better than it is right now.

“I just want to shine that light on nurses and turn up the volume so that they are part of every conversation,” says Jones, who crisscrossed the country to interview more than 100 nurses for The American Nurse: Photographs and Interviews by Carolyn Jones, a coffee-table book published in 2012 that includes the nurses in the documentary.

The nurses featured in the film include: Brian McMillion, MSN, MBA-HCM, RN, at the Veterans Health Administration San Diego Medical Center; Sister Stephen Bloesl, RN, from the Villa Loretto Nursing Home in Mount Calvary, Wisconsin; Tonia Faust, RN, CCN/M, from the Louisiana State Penitentiary; Naomi Cross, RN, from The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore; and Jason Short, BSN, RN, with Appalachian Hospice Care in Kentucky.

The film follows the path of nurses in different practice specialties, debunks common misconceptions about nurses, and raises questions for society about the challenges of healing America, say the five nurses spotlighted in the film. The featured nurses say they hope the documentary, praised by the White House, The American Journal of Nursing, and national media, educates audiences about their professionalism and the complexity of their roles.

For McMillion, coordinator of the Caregiver Support Program and VA clinical services director, the film is an opportunity to rebrand the profession. The documentary counters the unflattering and unrealistic media portrayals such as Nurse Jackie and raises awareness about stereotypes, says the Army vet and former medic who rehabilitates wounded soldiers returning from war. “We still hear ‘male nurse’ rather than just ‘nurse,’” McMillion says, chuckling. “When I was in school, people used to ask, ‘Are you studying to be a male nurse?’ and I would say, ‘Oh, no, I don’t need to study anymore to be a male; I have pretty much mastered that. I am studying to be a nurse.’”

The film will help the public realize that nurses work outside the hospital and toil deep in the community, says McMillion. (His third title is Major McMillion, 144th Minimal Care Detachment Commander.) “We are in the most intimate places, like their homes, and sometimes we are out in tents taking care of homeless people, which is an outreach I participate in every year as the VA clinical services director. I hope we can show people this is a profession that doesn’t require gender and that it has compassion, critical thinking, and technical proficiency requirements.”

McMillion was most impressed that the film crew, which followed him to Germany and a homeless center, was able to “translate the heart and humor of our profession in a masterful way.”

One message that Sister Stephen, director of nursing at Villa Loretto Nursing Home and president of the home’s board of directors, hopes viewers walk away with is that the nursing home industry is working hard to make care resident-centered. She runs a nursing home filled with goats, sheep, llamas, and chickens. It’s a place where the entire nursing staff comes together to sing for a dying resident.

“In my small, religious nursing home, we feel we can make the remaining years quality. We can be there with them and the families at the end of their life and offer them whatever comfort we can, whatever love we can, and assurance [that] there is an eternity for them, a beautiful life afterwards. If you look at it from a religious point of view, we are the hands and hearts of Jesus reaching out to these people. That’s what it’s all about for me,” says Sister Stephen, who is also president of Cristo Rey, a respite program for special needs children.

Sister Stephen, who has worked at the Villa Loretto Nursing Home since 1965, credited making the film and book projects with adjusting her attitude. “At one time, I was disillusioned with nursing because at times it is so non-hands-on, especially if you are in an administrative [position] or management. So many hours are devoted to paperwork,” she says. But after talking with many of the nurses featured in the book and attending related events, “I think, ‘Wow, I am really back on board.’ I tell people to really see what a gift they can be, what a service they can be to whatever area they decide to go in.”

The documentary also explores the work of a nurse inside a prison. Jones says she wanted to understand how a nurse can take care of people who committed horrible crimes. Tonia Faust, hospice program coordinator, has addressed that question numerous times during the 13 years she has worked at Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, the country’s largest maximum security facility. Faust, who runs a prison hospice program where inmates serving life sentences care for their fellow inmates as they’re dying, says treating prisoners requires skills, not judgment.

“I don’t actively look to see what their crimes are. My first year, I looked in the guys’ jackets to see what they did and sometimes I was shocked,” she recalls. “I thought, ‘I don’t need to do this for fear I may not treat them the way I am supposed to.’ Over the years, I realized people make mistakes in their lives. People don’t have the same upbringing as others.

“Some people may not have a choice. They have gone through the court system and been sentenced. It’s not my part to judge them or hold it against them. It could be my brother, my father, or me or my children in a prison. I look at them as patients, and my job is not to judge them, but to take care of them as best as I can with the skills I have learned through my education.”

One common misconception the public has about nurses is that their role is limited with the doctor making all of the decisions about care, says Naomi Cross, a labor and delivery nurse and the perinatal bereavement coordinator at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. In the film, Cross coaches patient Becky, an ovarian cancer survivor, through the cesarean delivery of her son. “I had a patient two days ago who had a complicated cancer, and we were going to deliver her baby early. I spent four hours preparing her for surgery and coordinated the doctors and other team members, about 15 people that took care of her during her surgery.

“I remember I am holding her hand, and we are about to put her under, and I’m telling her everything will be OK. And she said, ‘I didn’t know you were going to come with me. I didn’t know you did all these things.’ She was surprised by the whole view of what nursing does. So many times people have said, ‘I thought the doctor did that.’ The biggest misconception is how skilled, intelligent, and knowledgeable we are. I get that so much from my patients. They are always surprised . . . by our expertise.”

The film provides the audience an honest portrayal of the men and women who spend the most time with patients, says Jason Short, who works for Appalachian Hospice Care. Short provides home care to patients in eastern Kentucky, one of the poorest areas in the nation. The film shows him driving up a creek to reach a home-bound cancer patient in Appalachia.

“What I like about [The American Nurse], it captures the journey. It’s almost like nursing has been lost. And I think this was unique because all of us in the film, we are allowed the opportunity to do what nurses do, and that’s just care for people,” says Short, a former auto mechanic who is currently studying to become a nurse practitioner.

A nurse since 2007, Short was drawn to the field after a terrible motorcycle accident at age 18 and he “found out what it’s like to be helpless” and in need of compassionate care.

For Jones, the film, book, and online videos share the inspiring stories of the women and men who have pledged their lives to the care of others. Her desire to elevate and celebrate the nation’s most trusted professionals and their calling also stemmed, in part, from a life-altering experience with the nurse who administered her chemotherapy for breast cancer back in 2004. The memory left an indelible impression.

“The book was an idea brought to me by Fresenius Kabi USA [a global health care company]. This is what I love to do, take pictures and interview people. They wanted to do something to celebrate nurses. I had a nurse who got me through chemotherapy, and she was incredible. Once it was all finished, I never really thanked her properly,” recalls Jones. Over the years, “I thought of her many times. I think you go through an illness like that and you don’t want to turn around and relive it. I thanked her at the time, but not enough, and she never knew how much it meant to me.”

So when approached with the idea, Jones embraced it. The book, website, and accompanying online videos were a hit with nurses. Accolades flowed. Yet, Jones felt her mission was incomplete. “I learned so much doing the book about what role nurses serve in society, that I felt I wanted to do something that could really broadly reach the public. Nurses have enjoyed the book greatly; it’s about nurses, and it’s very much for nurses. It was to celebrate nurses. But I didn’t feel like I was really able to cross that threshold into the realm of the public and let the public really see and know what nurses do, and so that became my driving passion.

“The other reason is I wasn’t ready to leave this world of nurses.”