Teen suicide is a hidden epidemic in the United States. It is often overlooked by health care providers, parents and teachers because of the belief that suicide is something that happens to other people’s patients or children. No one wants to believe that adolescents are capable of taking their own lives. The statistics, however, reveal a different story. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the suicide rate in young people has increased dramatically over the past several decades. Overall, suicide is the third leading cause of death for young people aged 10 to 24.

Suicide, as a potentially preventable public health issue, is an area where nurses can play a critical role. Because nurses are positioned on the front lines of hospitals, public health facilities and schools, they often are the first people to come in contact with depressed or suicidal teens. And because adolescents are more likely to open up to a person of their own racial or ethnic group about their depression, dysfunctional family, substance abuse or suicidal thoughts, minority nurses can play a crucial role in slowing this alarming trend.

As the racial and ethnic makeup of our country continues to diversify, and as the rates of minority teen suicides continue to grow, America currently needs culturally competent nurses who can be on the look out for at-risk minority adolescents.

A Growing Threat for Minority Teens

It is often assumed that suicide is mainly an issue for white male teens. In reality, it affects both genders and all racial and ethnic groups. While more than four times as many men than women die from suicide, women are at a substantial risk—they attempt suicide about two to three times as often as men. And although white males commit suicide in the largest numbers overall, minority teen suicide numbers are climbing.

From 1979 to 1992, suicide rates for American Indians/Alaskan Natives (AI/ANs) were about 1.5 times higher than the national rate. There was a disproportionate number of suicides among young male AI/ANs during this period as well—male teens accounted for 64% of all suicides by AI/ANs, according to the CDC.

Suicide rates are also on the rise for African-American teens: From 1980 through 1996, suicide increased most rapidly (105%) among young black males ages 15 to 19.

According to in a survey of 151 high schools around the country by the Children’s Safety Network National Injury and Violence Prevention Resource Center (CSN), Hispanic students (10.7%) were more likely than white students (6.3%) to have made a prior suicide attempt.

Suicide and depression rates are increasing for Asian-American adolescents as well. Asian-American girls have the highest rates of depressive symptoms of all racial, ethnic and gender groups. Among women 15 to 24, Asian Americans have the second highest suicide mortality rates, according to the National Asian Women’s Health Organization.

It has also been widely reported that gay and lesbian youths are two to three times more likely to commit suicide than other teens and that 30% of all teen suicides or suicide attempts are related to issues of sexual identity. Although there is currently no empirical data to support these claims, the CSN feels there is a growing concern about the connection between suicide risk and bisexual or homosexual youth.

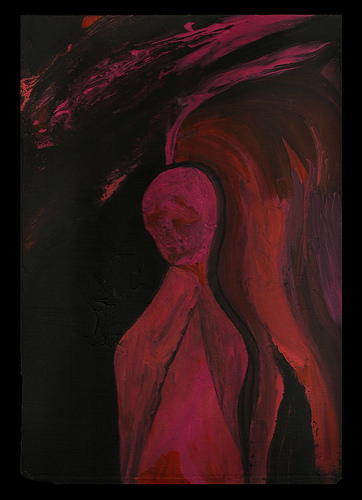

The Loss of Hope

“Back in the ‘60s, there was no such thing as suicide among black people,” states Faye A. Gary, RN, EdD, FAAN, distinguished professor at the University of Florida School of Nursing in Gainesville and a leading expert in the field of mental health nursing. “[There are more black suicides today] because of the deterioration of communities, the invasion of drugs, the weakening of the family structure and the decline of one’s sense of identity. Overall, there is a loss of hope,” says Gary, who is African American. This loss of hope, she asserts, stems from social issues like “poor education, limited job opportunities, poor health care and a distrust of the institutions that are designed to take care of us, like the police and schools.”

Bette Keltner, RN, PhD, dean of Georgetown University’s School of Nursing in Washington, D.C., and a past president of the National Alaskan Native/American Indian Nurses Association, believes similar issues are causing depression in AI/AN teens. The lack of jobs and recreational activities on the reservation, coupled with a general feeling of disenfranchisement, leads to depression and despair, she explains.

“Although the U.S. went through an economic boom in the ‘90s,” Keltner says, “people on the reservation are still living with an 80% unemployment rate. That is even more demoralizing than it was a few generations ago, when many Americans were unemployed. Native American youths are looking around at their community and realizing that their future doesn’t look very good.”

“The heart of the issue is the fracturing of the family, cultural values and sense of community, and that isn’t unique to any one [ethnic or racial] group—it could be said for everyone,” states June Strickland, RN, PhD, associate professor of Psychosocial Community Health at the University of Washington School of Nursing in Seattle.

According to the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), all teens deal with feelings of stress, confusion, self-doubt, financial uncertainty and pressure to succeed, regardless of race or ethnicity.

On the Front Lines

For some adolescents, a stressful living environment, coupled with typical teenage pressures, can result in clinical depression, other mental disorders or substance abuse, all of which can lead to suicide. According to the Surgeon General’s mental health report, over 90% of children and adolescents who kill themselves are suffering from depression or another mental or substance abuse disorder. However, these psychiatric conditions are highly treatable. More than 80% of people with clinical depression can be successfully treated with medication, psychotherapy or a combination of both according to the National Mental Health Association (NMHA).

Early recognition of depression in teens is vitally important in preventing the onset of serious depression or suicide. Minority nurses who come in contact with teens during emergencies, routine check-ups or in schools, are in the perfect position to recognize signs and symptoms of depression early on and alert parents to the need for immediate intervention.

“Nurses are close to the people most at risk; whether we are in the emergency room, public health clinics or schools, we are on the front lines, which is very important,” Keltner says. “And as a minority nurse, you have a greater opportunity for connection and communication [with teens who are not part of the major population].”

This is particularly important because in many cultures, mental illness and depression are viewed as signs of weakness, especially among males. The stigma attached to depression, coupled with the general lethargy many depressed patients experience, may lead suicidal teens to avoid seeking treatment.

Dorothy Marks, RN Med, a school nurse in the Chicago area, believes her position makes her more accessible to both students and parents. “I am fortunate because nurses are seen in a different light [than teachers and social workers],” she says. “We’re seen as someone who is there to help, someone who is approachable.” As an African-American nurse who grew up in the community in which she works, Marks is even more accessible. “I think it helps that I grew up in the community; I can relate to many of the young people,” she explains. “I used to work at the elementary school as well, so I have [been their school nurse] from the cradle to high school. I always tell the student that we’re family.”

Depression and suicide are difficult issues for most people to discuss, making it harder to diagnose and treat. Strickland advocates a more positive approach. “I never use the word ‘suicide’ when talking to a depressed teen or their parents,” she says. “What kid wants to be labeled as a ‘suicide risk’?”

But that is not to say Strickland, who is Native American, isn’t actively addressing the issue of suicide in the reservation communities where she works. “When I talk to parents, I tell them their child is at risk for ending their life because they have a special gift—they are able to feel with more passion and depth than most people,” she explains. “I stress the need to support this young person, and I try to bring a spirit of wellness, not sickness, into the community.”

[Nan: please make the following section a sidebar.]

How to Spot a High-Risk Teen

As a school or clinical nurse, it’s important to look for telltale signs of seriously depressed or potentially suicidal teens. These can include:

• adolescents who are suddenly not interested in things they used to be interested in, such as sports or music;

• a reported change in eating or sleeping habits;

• drug or alcohol use;

• unusual neglect of personal appearance;

• complaints of physical symptoms that are often linked to emotions, such as stomachaches, headaches or fatigue.

Suicidal teens often display a sense of resignation about life. They begin to tie up loose ends, as if preparing for death, by giving away or discarding important possessions. “Often, adolescents do not display the typical outward signs of despair you might assume someone considering suicide would display,” Keltner says. She stresses that any teen who talks about suicide should be taken extremely seriously.

According to the NMHA, other issues for nurses to be aware of when assessing a patient’s risk for suicide are:

• a background of substance abuse or depression,

• family dysfunction or violence,

• delinquency at a young age and

• psychiatric disorders.

Teaching Nurses How to Care

Although it is certainly ideal for a depressed adolescent to receive health care from a nurse of their same racial or ethnic background, this is not always possible. During the current shortage of nurses, and even greater shortage of minority nurses, at-risk teens will often come in contact with nurses of racial or ethnic groups other than their own. To provide culturally competent care to all patients, including depressed or suicidal teens, Gary advocates in-depth diversity training for nurses.

Strickland agrees, “We need to prepare all nurses to work with diverse populations. We are currently not doing enough. [Diversity training classes] should not be electives; they should be integrated throughout all course work.”

Nurses who are planning to specialize in providing health care to a specific population need comprehensive training to gain experience with the particular culture’s health care beliefs and practices. Rosalyn Harris-Offutt, CRNA, BS, LPC, LNC, ADS-UNA, who is African American and a First Nation Person (her preferred term for Native American), concurs that there is a need for more educated and open-minded nurses. “First Nation People need health care providers who are willing to work with non-Western healers and who are willing to learn about our methods of healing,” she says.

Not only do typically underserved populations need nurses who are willing to learn about and embrace cultures other than their own, they also need nurses who are willing to relocate to areas were health care services are limited. Native American communities, Harris-Offutt explains, are in desperate need of nurses willing to work in the isolated areas where reservations are often located. “In more remote places, teens who are in need of help can be very far apart,” she states. AI/AN adolescents may be unable to receive the mental health care they need because they are unable to get to a health care facility.

Keltner agrees that there is not enough access to mental health care in areas where typically underserved minority populations reside. “The question of access is really three questions,” she says. “First, is [mental health care] present at all? Is it of good quality? And is it accessible to the community?”

In addition to cultural competency training, nurses interested in working specifically with adolescents in the area of suicide prevention or depression treatment should also gain experience in mental health nursing, substance abuse programs, crisis management and adolescent development. Keltner believes nurses must have comprehensive educational preparation to be ready to handle the challenges of this at-risk population.

“If your nursing career focus will be with at-risk adolescents, you need professional preparation,” Strickland says. “It’s serious work. If you’re interested in it, you should follow that track in your education.”

Making a Difference in Your Community

Even though working in suicide prevention may not be the perfect career fit for every nurse, Strickland says there are many different ways nurses can help high-risk teens. By always remaining on the lookout for teens at risk for serious depression or suicide, you can also make a difference in saving young lives.

“We need community focused, broad-based prevention work in mental health to combat adolescent suicide,” explains Strickland. “You need to ask yourself, as a concerned member of your community, what can I do to support local young people? They need recreation and fun things to do to lift their spirits.”

Keltner adds, “Preventive, proactive programs that provide activities for kids where they can be successful, productive, valued and affirmed can make all the difference in the world.”

A Call To Action

Based on the startling statistics of increased suicide rates among minority teens, Surgeon General David Satcher, who is African American, recently issued a Call to Action to Prevent Suicide, which identifies suicide as a major public health issue. As part of the Healthy People 2010 Objectives, it sets a goal to significantly reduce suicide and suicide attempts among adolescents in grades 9 through 12 by the year 2010.

Satcher’s Call to Action recommends the following three steps to reduce suicide rates:

• Awareness—Public health professionals are encouraged to broaden the public’s awareness of suicide and its risk factors.

• Intervention—Services and programs aimed at preventing suicide must be enhanced.

• Methodology—The science and research behind suicide prevention must also be increased.

Minority nurses can play a vital role in accomplishing Satcher’s objectives. According to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General, racial and ethnic backgrounds need to be considered when treating teens who are depressed or suicidal. “Cultural differences exacerbate the general problems of access to appropriate mental health services,” the report states.

- Providing Cultural Competency Training for Your Nursing Staff - February 15, 2016

- Cultural Competence from the Patient’s Perspective - February 11, 2016

- Careers in Nephrology Nursing - February 10, 2016